Below is a virtual guide to the exhibition The Ese’Eja People of the Amazon: Connected by a Thread, on display at the Old College Gallery, University of Delaware, from August 31, 2016 through December 9, 2016. Here you will find further information about the themes, photographs, and objects featured in the exhibit.

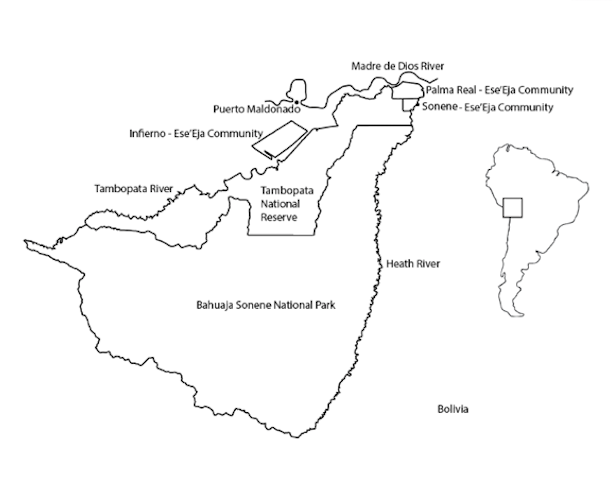

Believed to have descended from the sky on a thread of cotton, the Ese’Eja are one of the world’s last remaining foraging Amazonian cultures, and they are disappearing. They live in three communities along the Madre de Dios, Heath, and Tambopata rivers; the nearest city is Puerto Maldonado in Southeastern Peru. The Interoceanic Highway, which passes through Puerto Maldonado connecting ports in Brazil to those in Peru, has brought about 30,000 miners and loggers to the area surrounding the Ese’Eja lands. Their operations are threatening the Ese’Eja’s way of life. Through daguerreotypes and platinum-palladium prints created by Jon Cox and Andrew Bale, along with authentic material culture artifacts, this exhibition explores the worldview, ancestral lands, way of life, and contemporary challenges of this resilient society.

The Ese’Eja Ancenstral Lands

Jon Cox and Andrew Bale, Madre de Dios at Dawn, 2016, platinum palladium print, 12 x 8 in.

Since time immemorial the Ese’Eja have called the Amazon rainforest home. For centuries, they lived moving strategically through 1.2 million hectares of rainforest between the rivers Madre de Dios, Tambopata and Heath in Southeastern Peru. In the late nineteenth century, however, the region started to attract interest from outsiders: rubber barons in the late 1800s, Dominican missionaries in the 1920s and 1930s, Japanese refugees in the late 1940s, and more recently gold miners and loggers most of them operating illegally. These interventions gradually led to the sedentization of the Ese’Eja. In addition, governmental policies in the 1970s granting land rights to indigenous groups restricted the Ese’Eja nation to three residential villages: Infierno, Palma Real, and Sonene. Together these settlements only occupy about 23,000 hectares, a minimal fraction of the original Ese’Eja territory. With the creation of the Tambopata National Reserve and the Bahuaja-Sonene National Park in the 1990s, the Ese’Eja have been further restricted from accessing their traditional foraging grounds and sacred sites.

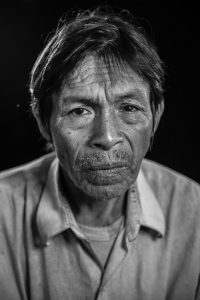

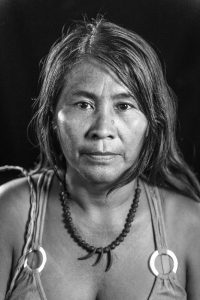

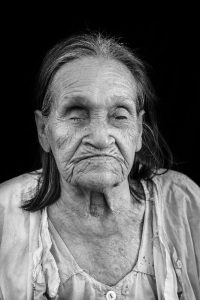

The True People

- Antonio

- Emilia

- Esperanza

- Pilar

- Mateo

- Adela

Like many other indigenous peoples in the Amazon, the Ese’Eja (or “The True People” as they call themselves), are affected by mercury that is being dumped into their environment as a byproduct of illegal gold mining. The mercury-developed, gold-gilded images of Ese’Eja community members created by Jon Cox and Andrew Bale draw attention to the mercury pollution being cast upon one of the world’s last remaining Amazonian cultures and the unique environment where they live.

Developed in 1839, daguerreotypes are the earliest photographic images, and have long been described as mirrors with a memory. When viewing each daguerreotype, you first see yourself reflected on the silver surface; and as you look deeper the portrait of an Ese’Eja becomes visible.

The Ese’Eja Worldview

Jon Cox and Andrew Bale, Down from a Cotton Thread, 2016, platinum palladium print, 8 x 12 in.

Ese’Eja oral histories reveal their deep spiritual connection with the rainforest. Many of the stories revolve around the spirits of the forest, known in the Ese’Eja language as edósikiana. They wear knee-long vests, crowns of red and yellow macaw feathers, face paint, and carry bows and arrows. The edósikiana have the power to transform an Ese’Eja into a shaman by shooting him with an arrow.

Healing and Medicinal Knowledge

Jon Cox and Andrew Bale, Mother and Child, 2016, platinum palladium print, 12 x 8 in.

In the past, the eyámikekwa or shamans cured individuals by using medicinal plants and making contact with the spirits of the forest (known in Ese’Eja language as edósikiana). Since the death of the last eyámikekwa in 1986, the Ese’Eja knowledge of medicinal plants and healing practices has been in decline. Pollution and deforestation have also brought unknown diseases to Ese’Eja settlements. Today community members have to resort to government-run care clinics, which are often inoperative due to staff shortages. If an emergency occurs, the closest healthcare services are located in Puerto Maldonado, several hours away and only accessible by boat.

The Ese’Eja Way of Life

Jon Cox and Andrew Bale, Brazil Nut Harvest, 2016, platinum palladium print, 8 x 12 in.

In their origins, the Ese’Eja relied on hunting, fishing and gathering for their survival. Using bows, arrows and a variety of handmade tools created with forest materials, they secured a diversity of foodstuffs. Through contact with outsiders, the Ese’Eja adopted the use of firearms, new fishing tools such as nets and hooks, as well as diverse farming methods. Excess products are now sold at markets in cities like Puerto Maldonado. Harvesting Brazil nuts for trade, in particular, has become a standard activity. In recent years, lack of access to areas of the rainforest where certain raw materials are available have made the Ese’Eja more dependent on manufactured goods from the outside world.

Learn more about the Ese’Eja material culture here.

Moving On

Jon Cox and Andrew Bale, Abandoned Eco-Lodge, 2016, platinum palladium print, 12 x 8 in.

In response to recent challenges, community members have sought out new survival strategies, such as an ecotourism lodge and a women’s artisanal co-op. These initiatives not only provide them with additional income for food and manufactured goods, but also for the education of younger generations who in the future could run local schools and health care facilities, and in the process preserve Ese’Eja ancestral knowledge and practices.